SIM Forum

SIM Forum is for sharing Strategic Instruction Model (SIM) ideas, views, articles, and more.

2025

This article was originally published in the StrateNotes Newsletter Vol. 33, No. 5 | May/June 2025

Making Learning Visible with SIM

Mary Black, SIM Professional Development Leader, North Carolina Jocelyn Washburn, Director of PD, KU CRL

John Hattie, Director of the Melbourne Educational Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia, presented his groundbreaking meta-analyses study in his first book Visible Learning for Teachers (2009). The Visible Learning research synthesizes findings from 1,500 meta-analyses of 90,000 studies involving 300 million students into what works best in education. The meta-analyses found that of the six groups of factors influencing successful learning in schools – the student, home, school, teacher, curricula and teaching – teachers seemed to have the strongest in-school effect. In 2023, Dr. Hattie published Visible Learning: The Sequel informed by more than 2,100 new meta-analyses about achievement drawn from more than 130,000 studies and conducted with the participation of more than 400 million students aged three to twenty-five, mainly from developed countries. It confirmed that certain high impact factors are still the most important factor when it comes to student learning. The factors (or influences on learning) also indicate the positive effect of teachers who focus on the impacts of their teaching and work together with other educators to critique their ideas about impact – about what was taught well, who was taught well and the size of the improvement.

Before the Visible Learning meta-analyses was conducted by John Hattie, researchers at KUCRL (beginning in 1978) developed The Strategic Instruction Model (SIM) as a comprehensive approach to adolescent literacy which also focused on the impact of teaching on learning, including an evidence-based set of instructional tools and interventions that empower teachers and enable students to better succeed in school and beyond. Strategic schools and teachers select instructional tools and interventions to meet their student needs, and strategic students have options for matching an approach to a task. The research-based components of these tools have been tested and approved by teachers to become evidence-based practices shown to be effective in varied school and classroom contexts. SIM includes two arms that work together to improve literacy: Learning Strategies (LS) and Content Enhancement Routines (CER). LS use explicit and systematic instructional procedures. CER implementation is supported by the SMARTER Instructional Cycle, an instructional planning cycle that promotes effective teaching and learning of critical content. Schools and teachers may implement a combination of LS and/or CER. SIM also includes two comprehensive reading programs, designed based on the science of reading: Fusion Reading (FR) and Xtreme Reading (XR).

Determining An Effect

When researchers conduct studies on the influence of an instructional tool on student outcomes, they can determine an effect size if a statistical difference is found during data analysis. To conduct the Visible Learning research, Hattie and his colleagues studied approximately 250 factors identified by prior research studies as having an impact on student achievement. Then, to determine which factors had the greatest impact, the researchers compared the effect sizes of all factors. An effect size can be defined as a standardized and scale-free measure of the relative size of the effect of an intervention--thus, the magnitude of an intervention’s effect or impact (Cohen, 1988; Kline, 2004). The greater the effect size, generally speaking, the greater the positive impact on student achievement.

Hattie determined that the effect size of d=0.40 was the hinge point, which meant the impact of teaching on student learning was the equivalent of one year of academic growth for one year of instruction by a teacher. Educators in a school must evaluate what equals a year of academic progress and measure impact with their shared consensus of progress. Therefore, using the effect size of d=0.40 as a key marker of influences on achievement amplifies real-world and powerful differences. However, it’s critical to note that effect sizes below d=0.40 should not be ignored, but rather a decision can be made to not look only at what works but also what works best. It is not a magical number but rather a guideline to begin discussion about what to aim for to see student growth in learning. Ninety percent of all effect sizes in education are positive (d > 0.0), and this means that almost everything works. Hattie reminds teachers that they should evaluate their teaching daily by asking, “What impact did I have on learning today?” They should create a student-focused classroom with high impact instruction where learning is visible.

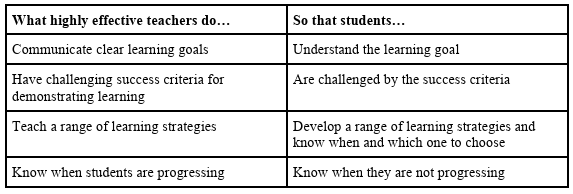

In 2017, Dr. John Hattie presented the Visible Learning research at the SIM International Conference at KUCRL. SIM professional developers attending the conference observed similarities between the findings of Hattie and his colleagues and the researchers at KUCRL and SIM tools for instruction and intervention. Both the Visible Learning influences and SIM focus on best practices for impact on student learning. In SIM professional learning sessions following the conference led by conference participants, teachers explored how the Learning Strategies and Content Enhancement Routines aligned with the Visible Learning influences with a demonstrated high impact on learning. The goal of the two educational models supported teachers in creating student-focused classrooms. Table 1 illustrates the influential relationship between teacher and student behaviors.

Examining Teacher Clarity

Central to the development of a student-focused classroom is the concept of teacher clarity. Frank Fendick (1990) defined teacher clarity as “a measure of the clarity of communication between teachers and students in both directions” (p. 10) and further described it across four dimensions:

● Clarity of organization - Tasks, assignments, and activities are aligned with goals of the learning and the assessments of learning.

● Clarity of explanation - Content conveyed must be relevant, accurate, and understandable to students and will move them to understanding their own level of learning.

● Clarity of examples and guided practice - Teachers provide intentional and purposeful examples and the opportunity for learners to practice building their capacity to become independent learners.

● Clarity of assessment - Assessments are used to generate evidence of learning and then use that feedback to give, receive, and integrate feedback into future learning. Three feedback questions from John Nottingham, one of Hattie’s colleagues, provides structure for the student feedback: What is my goal? What progress have I made toward that goal? What do I do next? Hattie stresses that students care most about the final question which prompts them to set their next learning goal (Almarode et al., 2025).

A Visible Learning and SIM Crosswalk

A crosswalk comparing select impact factors with SIM instructional principles is posted on the SIM Alignments webpage [https://sim.ku.edu/sim-alignment-other-programs-strategiesand-initiatives]. More specifically, the crosswalk examines how the dimensions of teacher clarity connect to the SIM tools and practices to help teachers and leaders in schools improve the twoway communication between teachers and students to boost student learning. The graphic in the crosswalk illustrates how teacher clarity (ES=0.75) relates in a domino effect of other Visible Learning influences from teacher-student relationships (ES=0.52) to assessment capable learners (ES=1.33).

While teacher clarity is foundational for the greatest impact on learning, Dr. Nancy Frey and Dr. Doug Fisher in Visible Learning for Literacy articulated three phases of student learning: surface, deep, and transfer (Frey et al., 2016). Considering the phases of student learning after a pre-assessment of their current knowledge and skills allows a teacher to design instruction with the right approach at the right time. During surface learning, students are acquiring knowledge and skills and then consolidating the content learned in order to move into deep learning. In deeper learning, students apply and use the knowledge and skills from their newly acquired content. Metacognitive strategies and close reading are complex tasks that require students to deepen their understanding. Finally, in the transfer phase, students focus on self-regulation of their learning, so they can accelerate their own learning. However, the phases aren’t linear, and teachers will create instruction matching students’ needs depending on data from frequent formative assessments.

In comparison, the SIM instructional tools maneuver students between all three learning phases as part of the evidence based instructional design. In the Learning Strategies, students take a pre-assessment, learn the new knowledge and skills and apply them in practice, and then move into the transfer phase with integration and generalization. Similarly, with the Content Enhancement Routines, teachers introduce new content at the surface level or the remembering and understanding level of Bloom’s Taxonomy with students and then transition to applying the new knowledge. At the end of a lesson, students consolidate their understanding in the transfer phase by applying the learning in a new and unfamiliar situation often including a real world one.

Call to Action

Click here to share feedback and your ideas with the authors.

References

Almarode, J., Fisher, D., Frey, N., and Barbee, K. (2025). Teacher clarity: Four necessary components for high impact student learning. Corwin Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied psychological measurement, 12(4), 425-434. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168801200410

Fendick, F. (1990). The correlation between teacher clarity of communication and student achievement gain: A meta-analysis. University of Florida. 3 StrateNotes Vol. 33, No. 5 | May/June 2025

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades K-12: Implementing the practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Corwin Press.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning, The sequel: A Synthesis of Over 2,100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Corwin Press.

Kline, R. B. (2004). Beyond significance testing: Reforming data analysis methods in behavioral research. American Psychological Association.

Additional Books to Explore

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Almarode, J., Barbee, K., Amador, O., & Assof, J. (2024). The teacher clarity playbook, grades K-12: A hands-on guide to creating learning intentions and success criteria for organized, effective instruction. Corwin Press.

Frey, N., Hattie, J., & Fisher, D. (2018). Developing assessment-capable visible learners, grades K-12: Maximizing skill, will, and thrill. Corwin Press.

2024

Spring 2024: SIM Educator Newsletter

- SIM Events & New Overview, p.1

- SIM Story Corps: Becoming a Better Teacher with SIM, p. 2-3

- Links to SIM Resources and Tools, p. 4

Fall 2024: SIM Educator Newsletter

- SIM Overview Podcast - created with AI

- Virtual Professional Learning for Educators in:

- Cross-Curricular Argumentation Routine

- Framing Routine

- Fundamentals of Paraphrasing and Summarizing Strategy

- The Paragraph Writing Strategy

- Possible Selves Strategy (1st or 2nd edition)

- Sentence Writing Strategies (Fundamentals and Proficiency)

- Unit Organizer Routine

- SIM Resources and Tools:

- 2024 HLP & SIM Crosswalk

- Manual Updates

- New Xtreme Reading Sampler

- Free Professional Learning Micro-Credentials

- Article: Providing a Continuum of Special Education Supports, Dana McCaleb (VA)

- Recent Podcasts, Publications, and Research Projects

2023

Fall 2023: SIM Educator Newsletter

- p1 - SIM Events & Links to New Brochures

- p. 2-4 - Enacting the IES Evidence-Based Recommendations for Reading Interventions with SIM™ Reading Strategies, Jocelyn Washburn

- p. 5-6 - Links to SIM Resources and Tools

Using the Decision-Making Routine for IEP and Post-Secondary Goal Development

Darren Minarik, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Radford University

SIM Content Enhancement Professional Developer

How can we help students with disabilities take ownership of their Individualized Education Program (IEP)? Research on transition planning over the last 20 years suggests that active student involvement in transition planning is essential to improve post-secondary outcomes (Martin & Zhang, 2020). One effective strategy to promote more active student involvement is the Decision-Making Routine. This research-driven device helps students narrow down their post-secondary goals and identify the services and support they need to reach them.

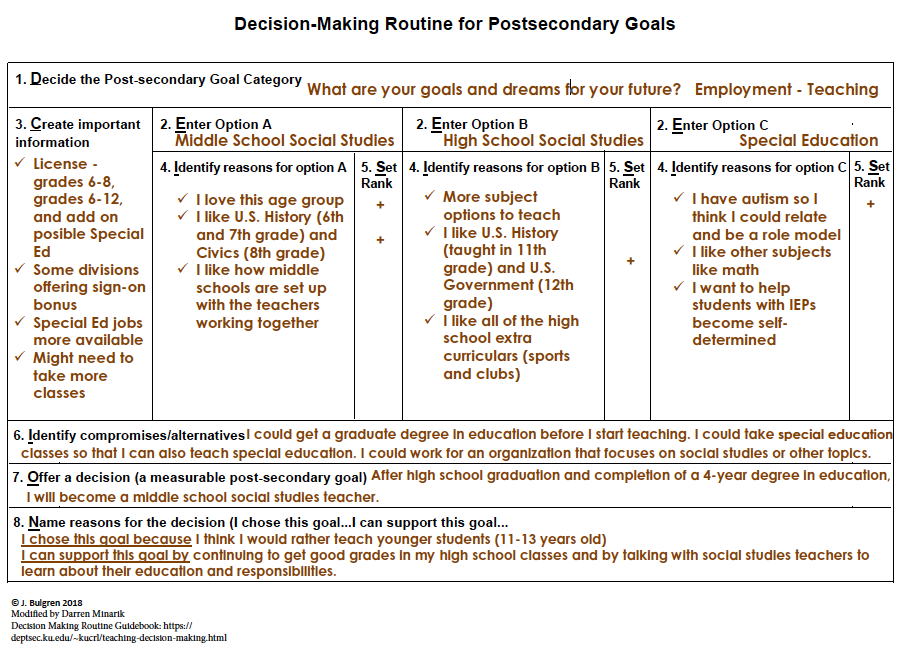

The Decision-Making Routine involves higher order thinking and reasoning when there are multiple options or ways to respond to a particular issue (Bulgren, 2018). This approach includes critical thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and judgment. The routine's linking steps spell out the word DECISION (see Table 1), providing an explicit structure that guides teachers and students during the interactive creation of the Decision-Making Routine. The teacher creates a draft routine in advance as a model, and then the device is co-constructed, allowing students to demonstrate their higher order thinking and reasoning skills as they participate in the final creation process. Following the Cue, Do, Review Sequence, the teacher cues the routine, follows the linking steps, and reviews the reasons for the final decision, frequently referring back to the content addressed throughout the course/year.

Table 1. Decision-making DECISION Linking Steps

Decide the issue Enter options Create a list of important information Identify reasons to support each option Set rank for each reason Identify compromises or alternatives Offer a decision Name reasons for the decision |

Source: Bulgren, J.A. (2018). Teaching decision-making. University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning.

When using the Decision-Making Routine for post-secondary goal development, students first Decide on the post-secondary goal category and ask themselves, "What are my goals and dreams for the future?" Then, the student participates in transition assessments to gather data on employment/career, education/training, and independent living/community participation post-secondary goals. In collaboration with the teacher, the student Enters the options identified through the transition assessment data.

After entering options, the student Creates a list of important information connected to the listed options. These items are typically pieces of information that a student needs to keep in mind, regardless of the option they choose. Then, the student goes through each option individually to Identify reasons to support each option.

The fourth step involves ranking the reasons listed in the options. When a student Sets the rank for each reason, it helps prioritize which option should become a post-secondary goal. A numbered system or pluses and minuses can be used to identify the most valued reasons.

During the first four linking steps, students may come across related topics or alternatives while researching their options. They may also realize that their options might be overly ambitious or will take longer to achieve. In this case, the Identify compromises and alternatives section of the device is used to list related topics or alternatives and to discuss any compromises that might be necessary.

The last two steps involve writing the post-secondary goals and explaining the reasoning for selecting certain goals. In the Offer a decision step, the student takes the selected option and writes a goal using one of the following sentence stems:

- After high school completion, I will…

- After graduation, I will…

- Following exit from age 18-21 transition services, I will...

- Within one year of completing high school, I will…

- After high school graduation and graduation from ___, I will….

Finally, the student Names reasons for choosing the goal and creates a series of "I" statements explaining why the post-secondary goal chosen fits with their goals and dreams for the future. The “I” statements also help explain the transition services needed in the next year to support the knowledge and skills necessary to reach their post-secondary goal. The student is answering the question, “What do I need to learn in a year to help me achieve my goal after graduation from high school?” Remember, transition services do not always need to be outside services or even services provided directly by school personnel. Students and their families can also provide transition services to support post-secondary goals.

Figure 1 provides a sample Decision-Making Routine examining an employment goal. Through transition assessment data, the student indicated that teaching was a future employment goal. Because the student is nearing graduation, a narrowing of the post-secondary goal was needed as choices were being made regarding post-secondary education. The student examined three options and also considered the possibility of working in a related education career.

Figure 1. Decision Making Routine for Post-secondary Goals

The Decision-Making Routine is an effective tool for helping students write their own post-secondary goals and sections of the Present Level of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance. This is an opportunity for students to exercise self-determination in the IEP process. By better understanding their hopes and dreams for the future and what it takes to reach those goals, students can be empowered to be independent and live dignified lives.

References

Bulgren, J. A. (2018). The Decision-Making Routine. University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning.

Martin, J., & Zhang, D. (2020). Student involvement in the transition process. In Handbook of adolescent transition education for youth with disabilities (pp. 120-137). Routledge.

Higher Order Thinking and Reasoning (HOTR) Routines Support Rigor

Craig Wisniewski, SIM Professional Developer

Regardless of if you are newer to the education profession or a seasoned veteran, you have undoubtedly experienced edu-speak—the use of acronyms and overused jargon. Acronyms and jargon such as AYP, RTI, SPED, grit, rigor, growth mindset, etc. are key elements in a student’s success but lose substantial meaning when reduced to edu-speak.

Rigor is an edu-speak term that is overly used in education, creating ambiguity. For some, rigor means increasing the difficulty of assignments, others believe it's providing additional work, and some cannot define it but know it when they see it (Sztabnik). Barbara Blackburn, in Rigor Is NOT a Four-Letter Word, defines rigor as “creating an environment in which each student is expected to learn at high levels, each is supported so he or she can learn at a high level, and each student demonstrates learning at a high level”.

The Higher Order Thinking and Reasoning Routines (HOTR), part of the Content Enhancement Routines from the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning, help students engage in the critical skills of higher order thinking and reasoning required by national and state standards. Each routine, in alignment with Blackburn’s definition, uses a familiar Cue, Do, Review instructional sequence to ensure educators are provided with rigorous learning opportunities for their students:

Instructional Sequence | What This Looks Like | Alignment to Blackburn’s Definition of Rigor | Example via the Concept Comparison Routine |

|

Providing an Overview of the Graphic Organizer and the Steps to Complete It | Creating an environment in which each student is expected to learn at high levels | The teacher announces the Comparison Table and explains its use and expectations for student participation |

|

Graphic Organizer is Co-Constructed by the Teacher and Students |

Each student is supported so he or she can learn at a high level | The teacher and class collaboratively construct the device using the COMPARING Linking Steps* that “connect” the content to the needs and goals of students. |

|

Teacher Checking for Understanding | Each student demonstrates learning at a high level

| Information presented in the Comparison Table is reviewed and confirmed, and the process of exploring similarities and differences between concepts is reviewed. |

*COMPARING Linking Steps

Communicate Targeted Concepts

Obtain the Overall Concepts

Make Lists of Known Characteristics

Pin down Like Characteristics

Assemble Like Characteristics

Record Unlike Characteristics

Identify Unlike Categories

Nail Down a Summary

Go Beyond the Basics

As evidenced via the Concept Comparison Routine in relation to Blackburn’s definition of rigor, students demonstrate the following critical thinking skills throughout the Do and Review stages of the Instructional Sequence for each HOTR Routine:

- utilize their schema to connect ideas,

- ask deep probing questions about a topic,

- identify and understand the importance of a topic, and

- utilize reflective thinking to continuously develop their understanding.

Other routines in the HOTR series include the Cause and Effect Routine, the Question Exploration Routine, the Decision-Making Routine, the Cross Curricular Argumentation Routine, and the Scientific Argumentation Routine. Each of these HOTR routines utilizes the Cue-Do-Review instructional sequence. Using HOTR routines helps educators create a rigorous classroom culture by defining what they want students to experience and achieve and by providing students with productive struggle opportunities.

References

Blackburn, Barbara R. Rigor Is NOT a Four-Letter Word. New York, NY, Routledge, 2018.

Sztabnik, Brian. “A New Definition of Rigor.” Edutopia, George Lucas Educational Foundation, 7 May 2015, www.edutopia.org/blog/a-new-definition-of-rigor-brian-sztabnik.